In Part 1 of the TwitterFiles, we learned that Twitter was working with politicians, federal agencies, and Biden’s campaign team to censor information on Twitter – specifically as related to Hunter Biden’s laptop and the ensuing New York Post story.

In Part 2, we learned that teams of Twitter employees build blacklists, prevent disfavored tweets from trending, and actively limit the visibility of entire accounts or even trending topics—all in secret, without informing users. In other words, “blacklisting” and “shadowbanning” were real, despite congressional testimony by people like Jack Dorsey claiming otherwise.

In Part 3, Matt Taibbi will reveal how Twitter employees and directors escalated their censorship campaign in January 2020… and how they effectively threw out the rulebook in favor of their own partisan ideals.

The world knows much of the story of what happened between riots at the Capitol on January 6th, and the removal of President Donald Trump from Twitter on January 8th. What isn’t known is the erosion of standards within the company in months before January 6th, decisions by high-ranking executives to violate their own policies, and more, against the backdrop of ongoing, documented interaction with federal agencies.

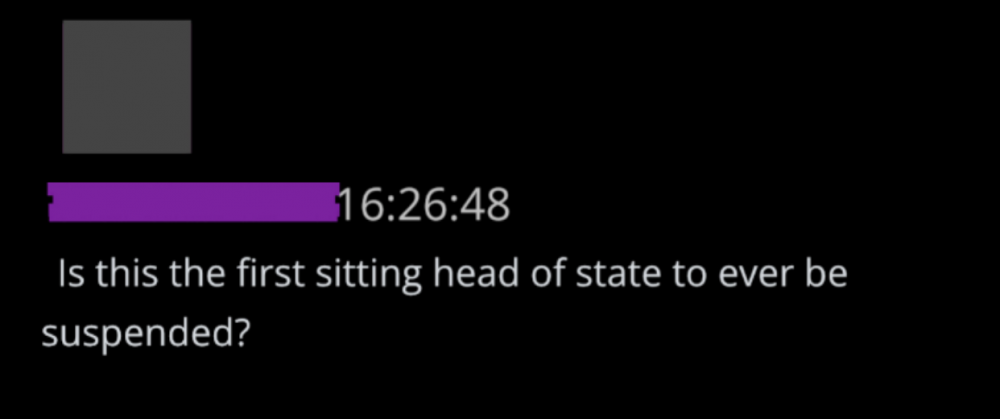

Whatever your opinion on the decision to remove Trump that day, the internal communications at Twitter between January 6th-January 8th have clear historical import. Even Twitter’s employees understood in the moment it was a landmark moment in the annals of speech.

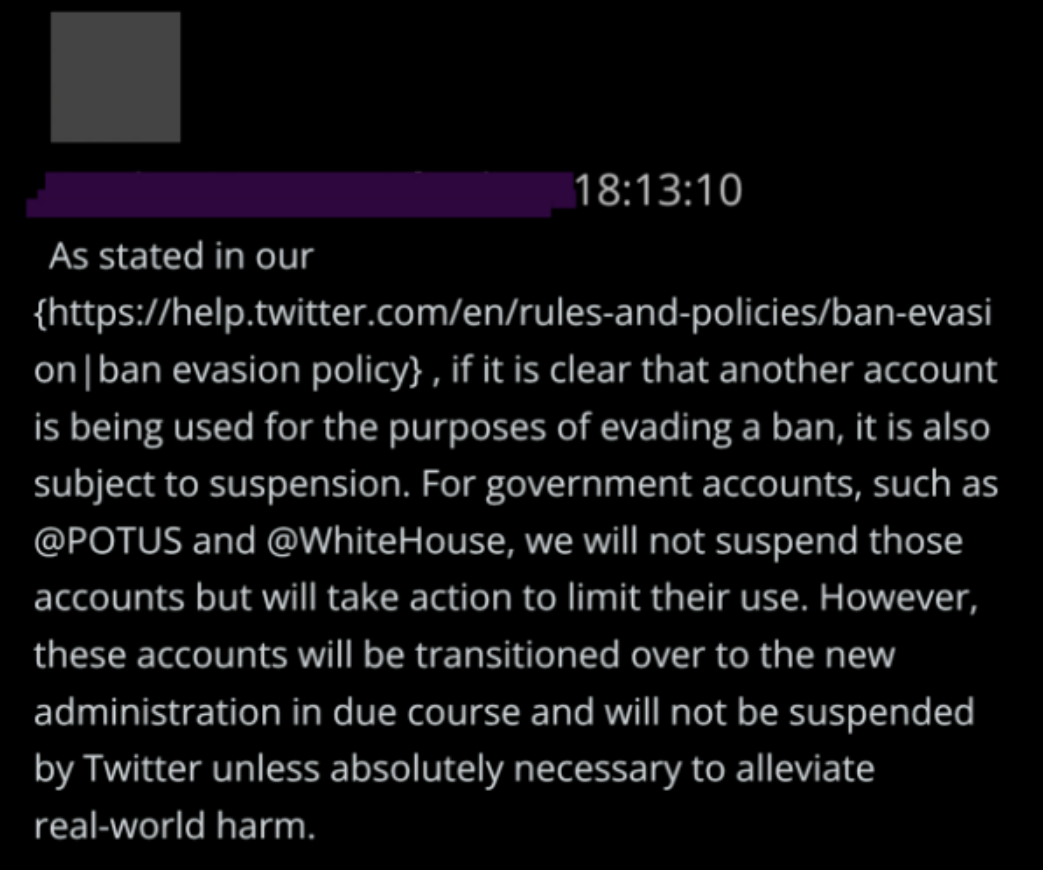

As soon as they finished banning Trump, Twitter execs started processing new power. They prepared to ban future presidents and White Houses – perhaps even Joe Biden. The “new administration,” says one exec, “will not be suspended by Twitter unless absolutely necessary.”

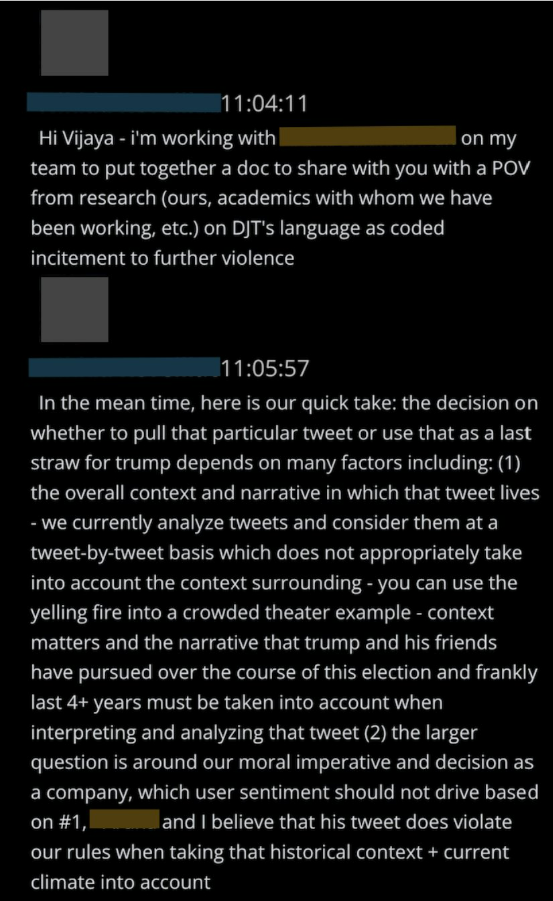

Twitter executives removed Trump in part over what one executive called the “context surrounding”: actions by Trump and supporters “over the course of the election and frankly last 4+ years.” In the end, they looked at a broad picture. But that approach can cut both ways.

The bulk of the internal debate leading to Trump’s ban took place in those three January days. However, the intellectual framework was laid in the months preceding the Capitol riots. Before January 6th, Twitter was a unique mix of automated, rules-based enforcement, and more subjective moderation by senior executives. As Bari Weiss reported, the firm had a vast array of tools for manipulating visibility, most all of which were thrown at Trump (and others) pre-January 6th.

As the election approached, senior executives – perhaps under pressure from federal agencies, with whom they met more as time progressed – increasingly struggled with rules, and began to speak of “vios” as pretexts to do what they’d likely have done anyway.

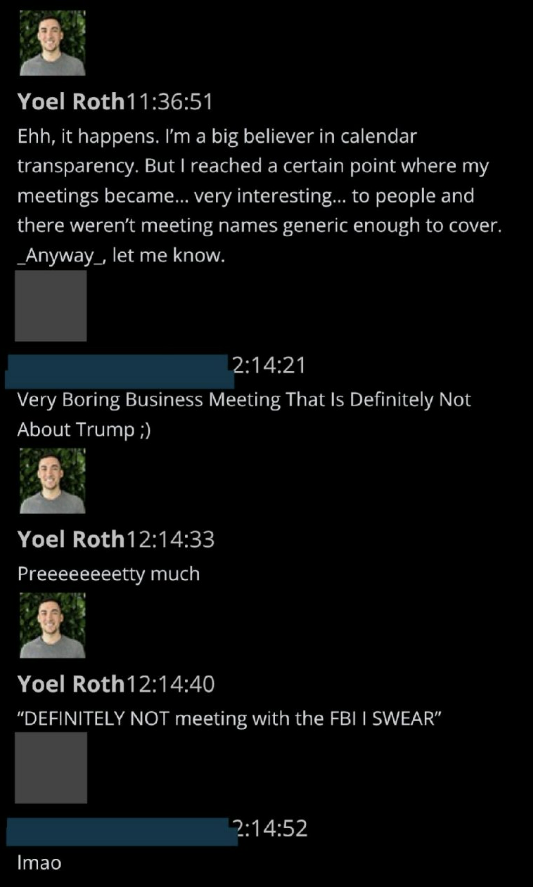

After J6, internal Slacks show Twitter executives getting a kick out of intensified relationships with federal agencies. Here’s Trust and Safety head Yoel Roth, lamenting a lack of “generic enough” calendar descriptions to conceal his “very interesting” meeting partners.

These initial reports are based on searches for docs linked to prominent executives, whose names are already public. They include Roth, former trust and policy chief Vijaya Gadde, and recently plank-walked Deputy General Counsel (and former top FBI lawyer) Jim Baker. One particular slack channel offers an unique window into the evolving thinking of top officials in late 2020 and early 2021…

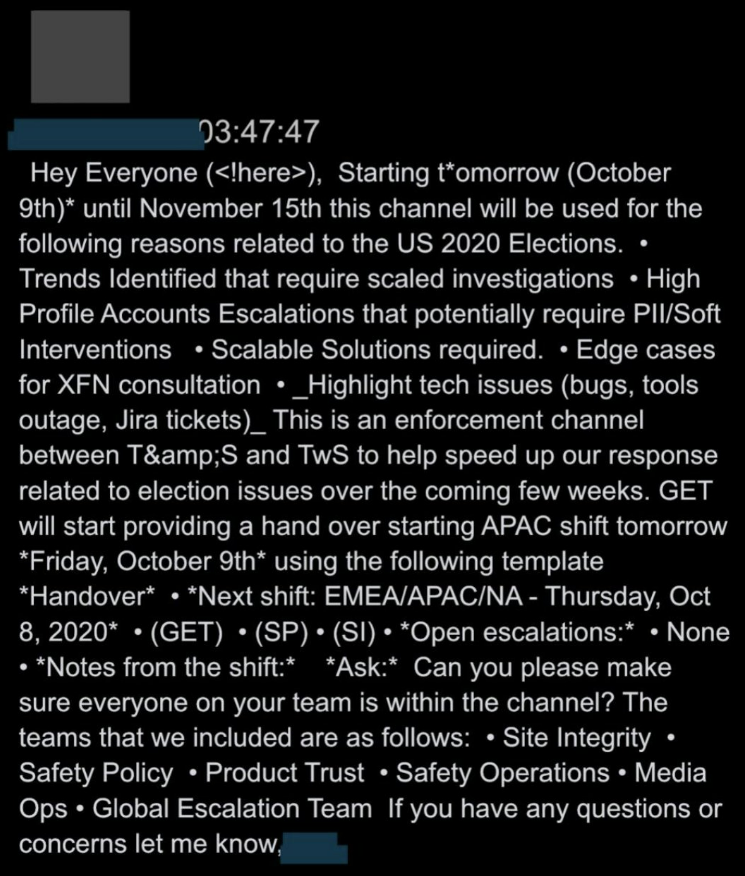

On October 8th, 2020, executives opened a channel called “us2020_xfn_enforcement.” Through J6, this would be home for discussions about election-related removals, especially ones that involved “high-profile” accounts (often called “VITs” or “Very Important Tweeters”).

There was at least some tension between Safety Operations – a larger department whose staffers used a more rules-based process for addressing issues like porn, scams, and threats – and a smaller, more powerful cadre of senior policy execs like Roth and Gadde.

The latter group were a high-speed “Supreme Court” of moderation, issuing content rulings on the fly, often in minutes and based on guesses, gut calls, even Google searches, even in cases involving the President.

During this time, executives were also clearly liaising with federal enforcement and intelligence agencies about moderation of election-related content. While we’re still at the start of reviewing the TwitterFiles, we’re finding out more about these interactions every day.

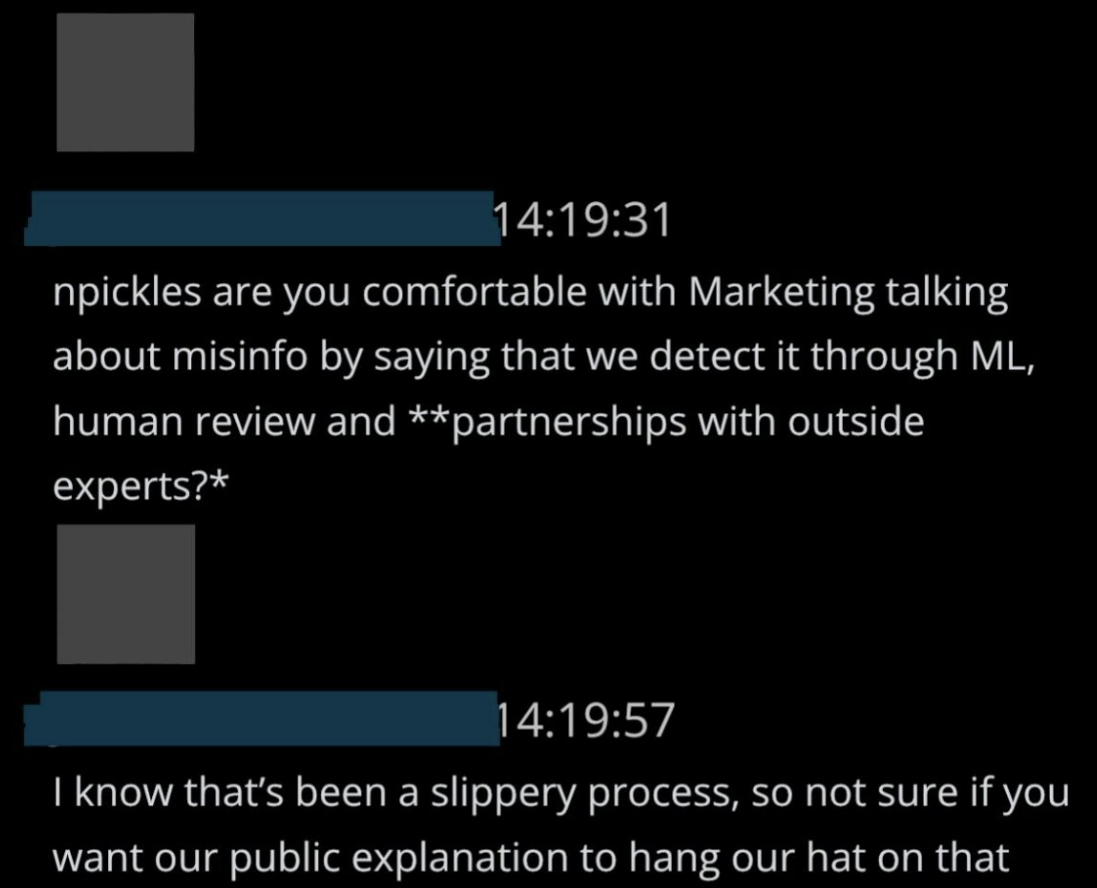

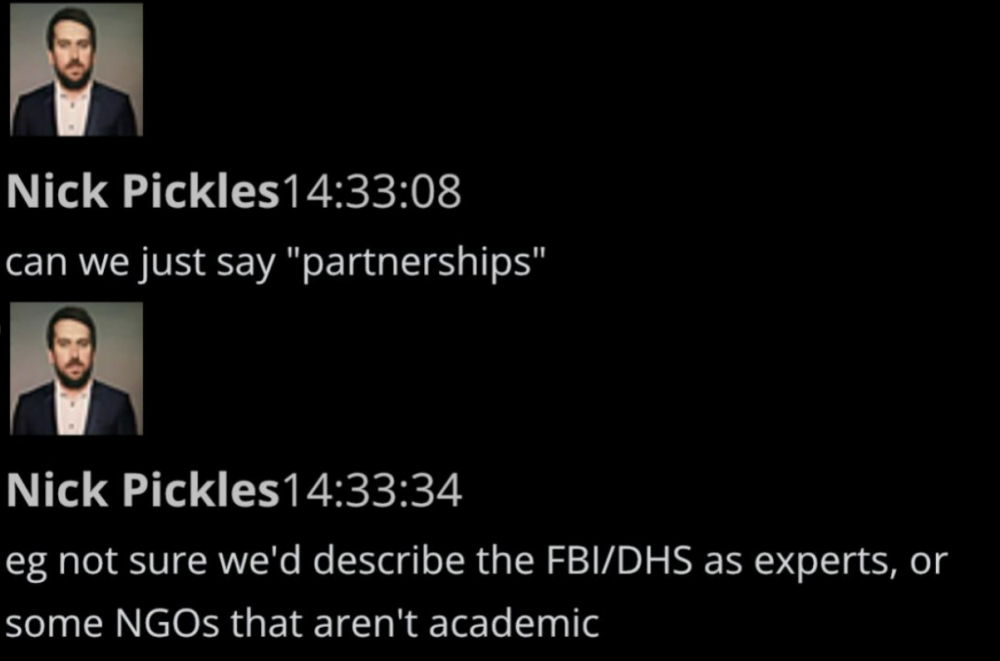

Policy Director Nick Pickles is asked if they should say Twitter detects “misinfo” through “ML, human review, and **partnerships with outside experts?*” The employee asks, “I know that’s been a slippery process… not sure if you want our public explanation to hang on that.”

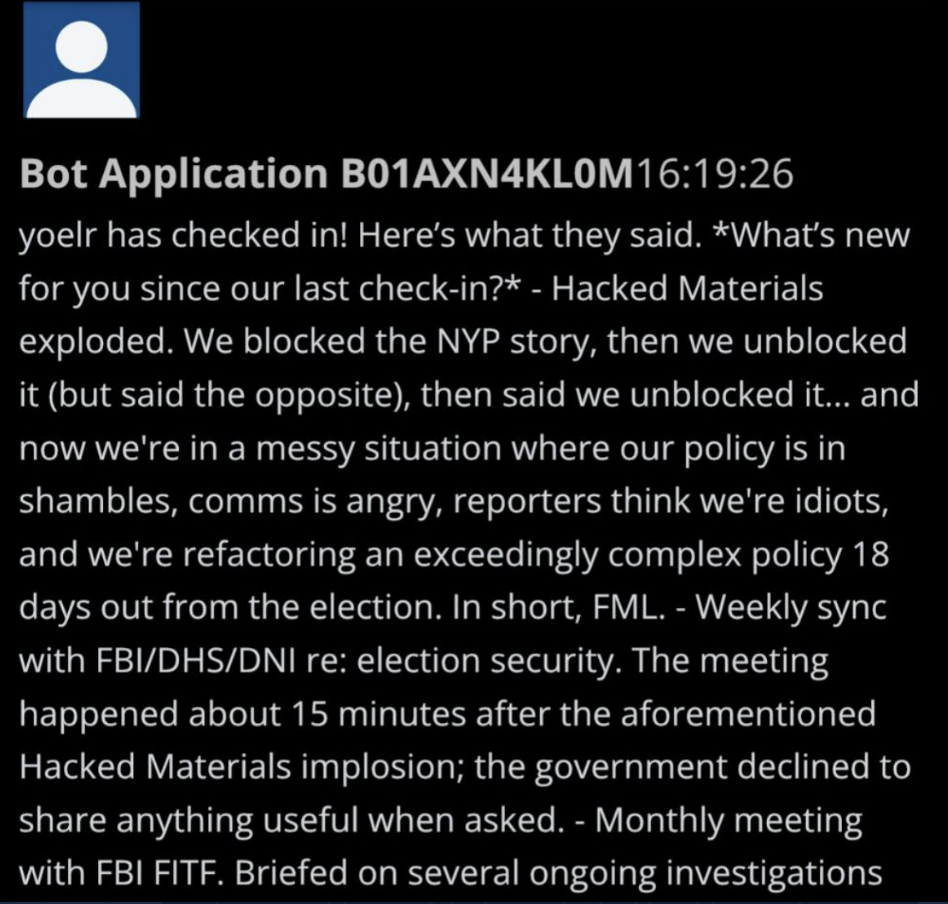

Pickles quickly asks if they could “just say “partnerships.” After a pause, he says, “e.g. not sure we’d describe the FBI/DHS as experts.” This post about the Hunter Biden laptop situation shows that Roth not only met weekly with the FBI and DHS, but with the Office of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI):

Roth’s report to FBI/DHS/DNI is almost farcical in its self-flagellating tone: “We blocked the NYP story, then unblocked it (but said the opposite)… comms is angry, reporters think we’re idiots… in short, FML” (f*ck my life).

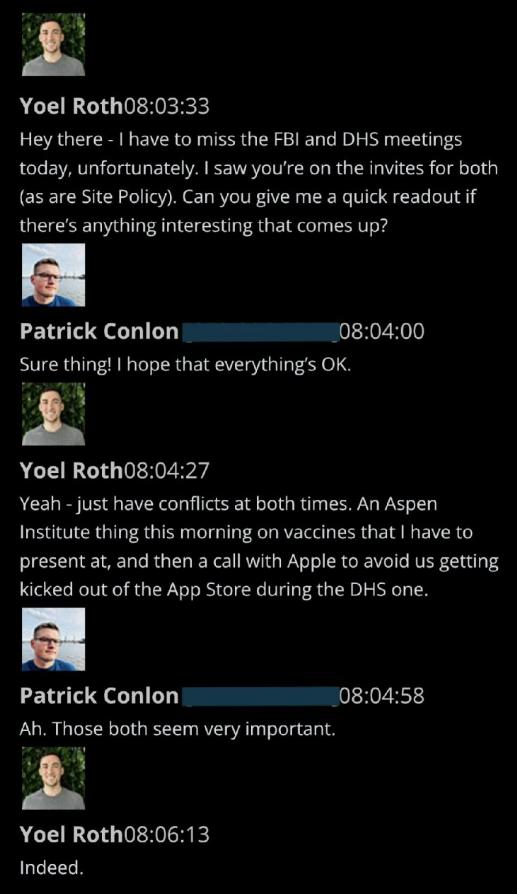

Some of Roth’s later Slacks indicate his weekly confabs with federal law enforcement involved separate meetings. Here, he ghosts the FBI and DHS, respectively, to go first to an “Aspen Institute thing,” then take a call with Apple.

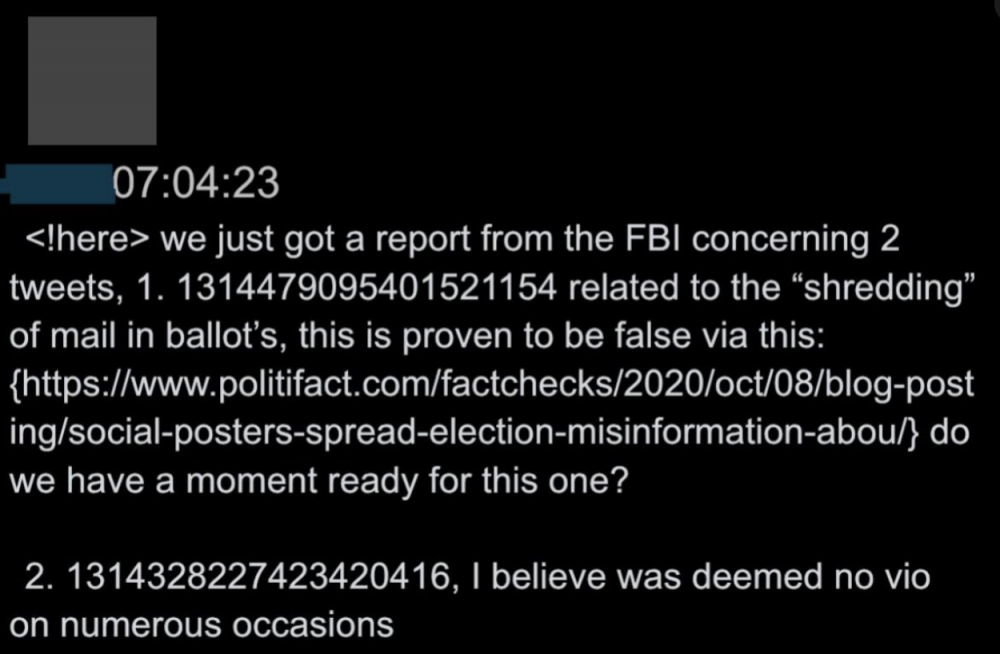

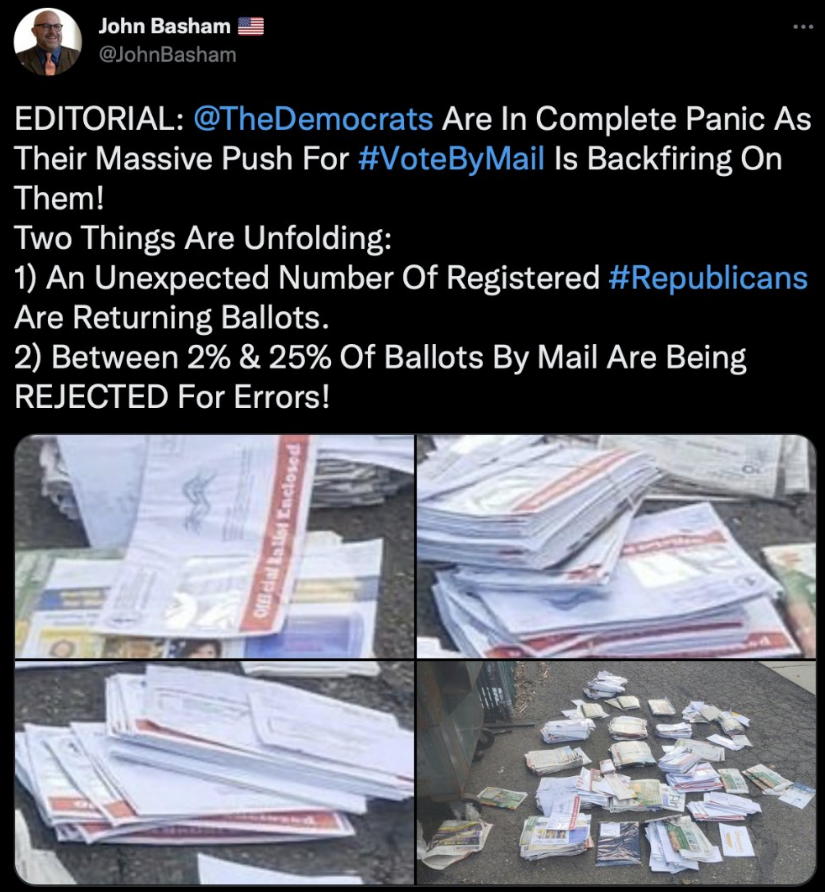

Here, the FBI sends reports about a pair of tweets, the second of which involves a former Tippecanoe County, Indiana Councilor and Republican named John Basham claiming “Between 2% and 25% of Ballots by Mail are Being Rejected for Errors.”

The FBI’s second report concerned this tweet by @JohnBasham:

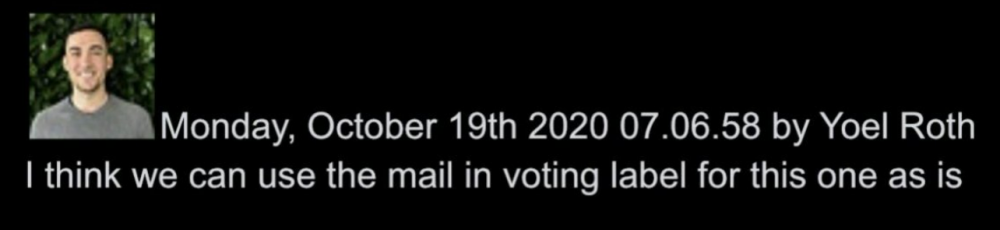

The FBI-flagged tweet then got circulated in the enforcement Slack. Twitter cited Politifact to say the first story was “proven to be false,” then noted the second was already deemed “no vio on numerous occasions.

”The group then decides to apply a “Learn how voting is safe and secure” label because one commenter says, “it’s totally normal to have a 2% error rate.” Roth then gives the final go-ahead to the process initiated by the FBI:

Examining the entire election enforcement Slack, we didn’t see one reference to moderation requests from the Trump campaign, the Trump White House, or Republicans generally. We looked. They may exist: we were told they do. However, they were absent here.

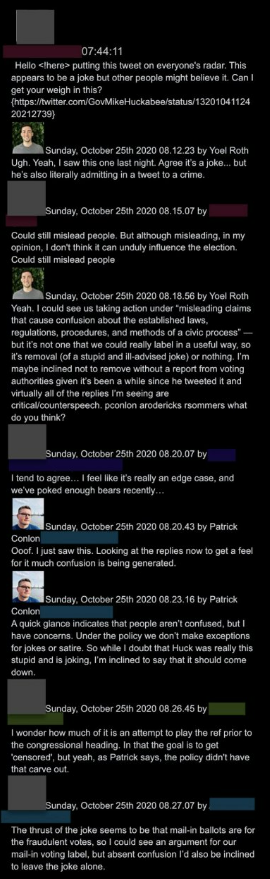

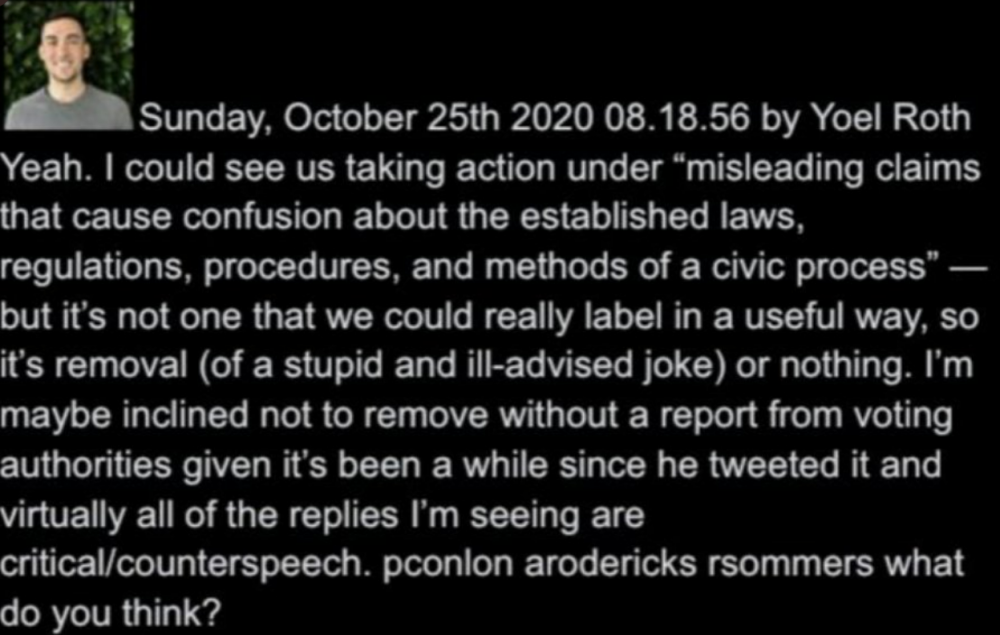

In one case, former Arizona governor Mike Huckabee joke-tweets about mailing in ballots for his “deceased parents and grandparents.” This inspires a long Slack that reads like an @TitaniaMcGrath parody. “I agree it’s a joke,” concedes a Twitter employee, “but he’s also literally admitting in a tweet a crime.”

The group declares Huck’s an “edge case,” and though one notes, “we don’t make exceptions for jokes or satire,” they ultimately decide to leave him be, because “we’ve poked enough bears.”

“Could still mislead people… could still mislead people,” the humor-averse group declares, before moving on from Huckabee.

Roth suggests moderation even in this absurd case could depend on whether or not the joke results in “confusion.” This seemingly silly case actually foreshadows serious later issues:

In the docs, execs often expand criteria to subjective issues like intent (yes, a video is authentic, but why was it shown?), orientation (was a banned tweet shown to condemn, or support?), or reception (did a joke cause “confusion”?). This reflex will become key in January 6th.

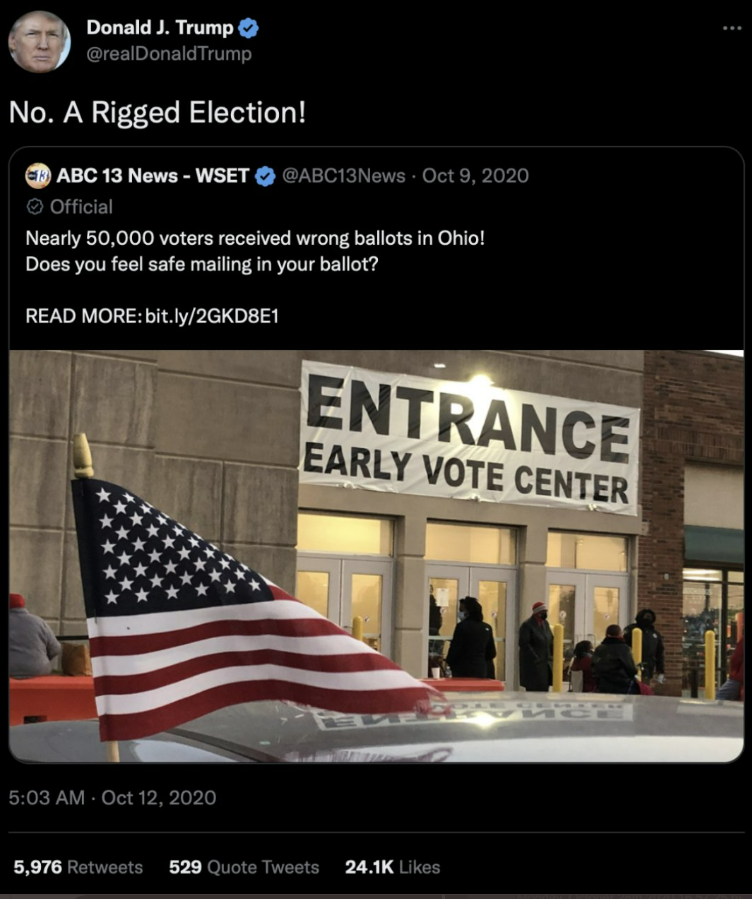

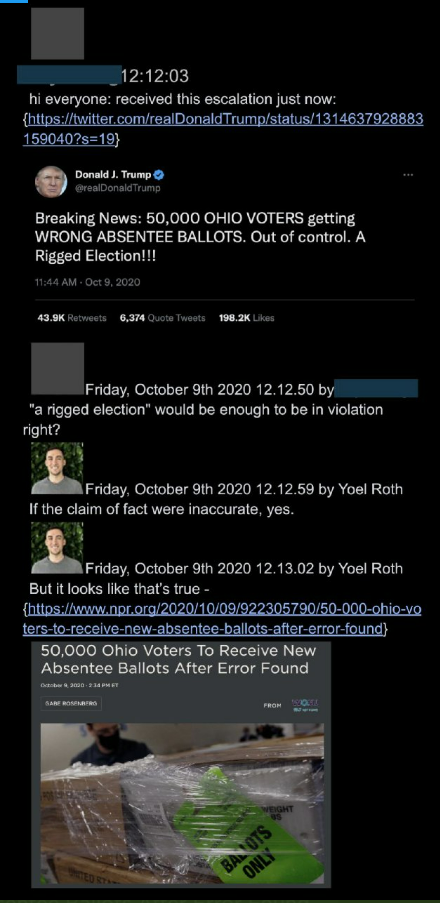

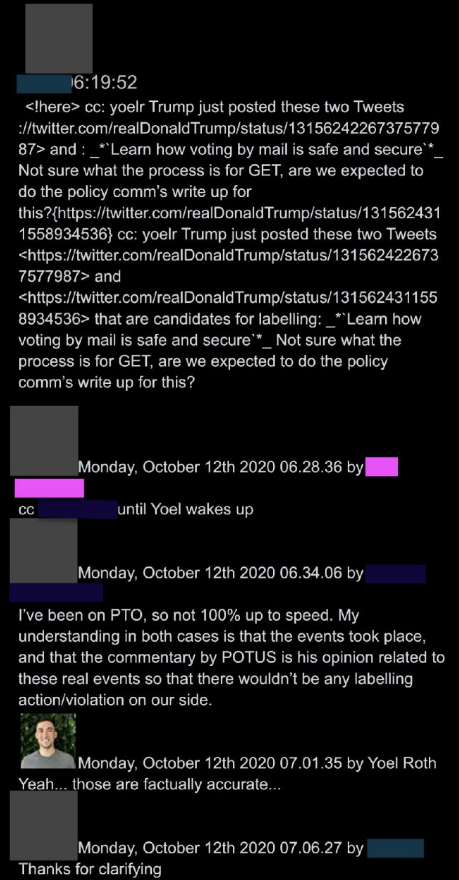

In another example, Twitter employees prepare to slap a “mail-in voting is safe” warning label on a Trump tweet about a postal screwup in Ohio, before realizing “the events took place,” which meant the tweet was “factually accurate”:

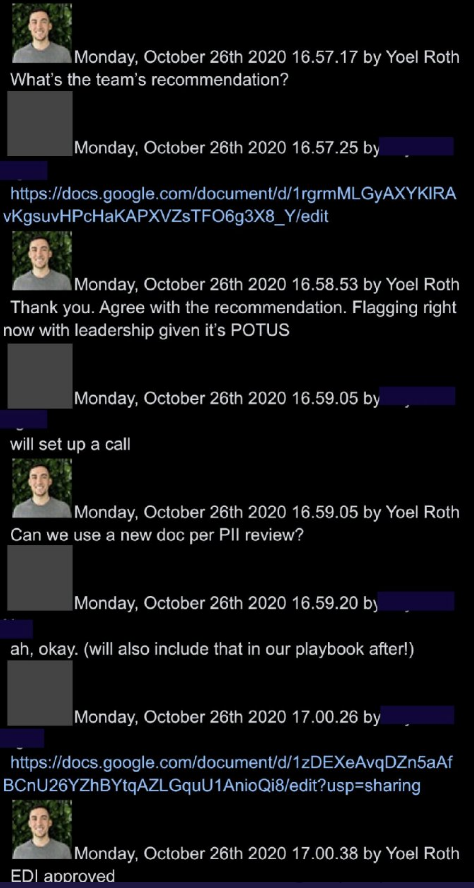

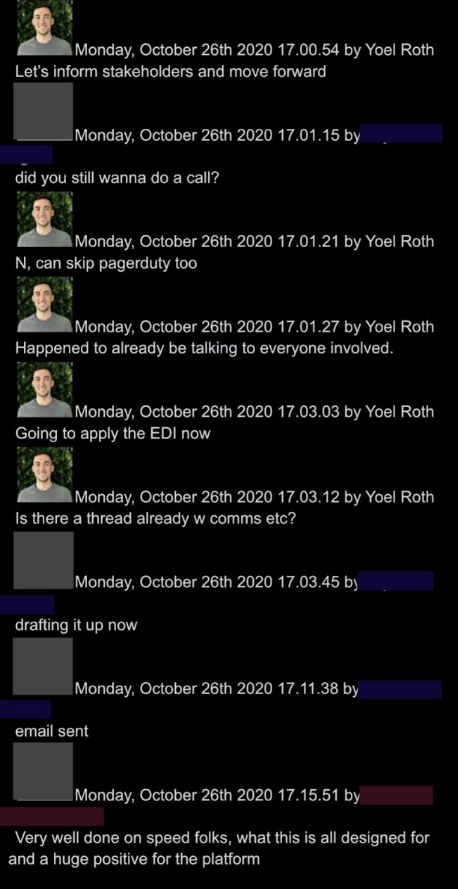

“VERY WELL DONE ON SPEED” Trump was being “visibility filtered” as late as a week before the election. Here, senior execs didn’t appear to have a particular violation, but still worked fast to make sure a fairly anodyne Trump tweet couldn’t be “replied to, shared, or liked”:

“VERY WELL DONE ON SPEED”: the group is pleased the Trump tweet is dealt with quickly.

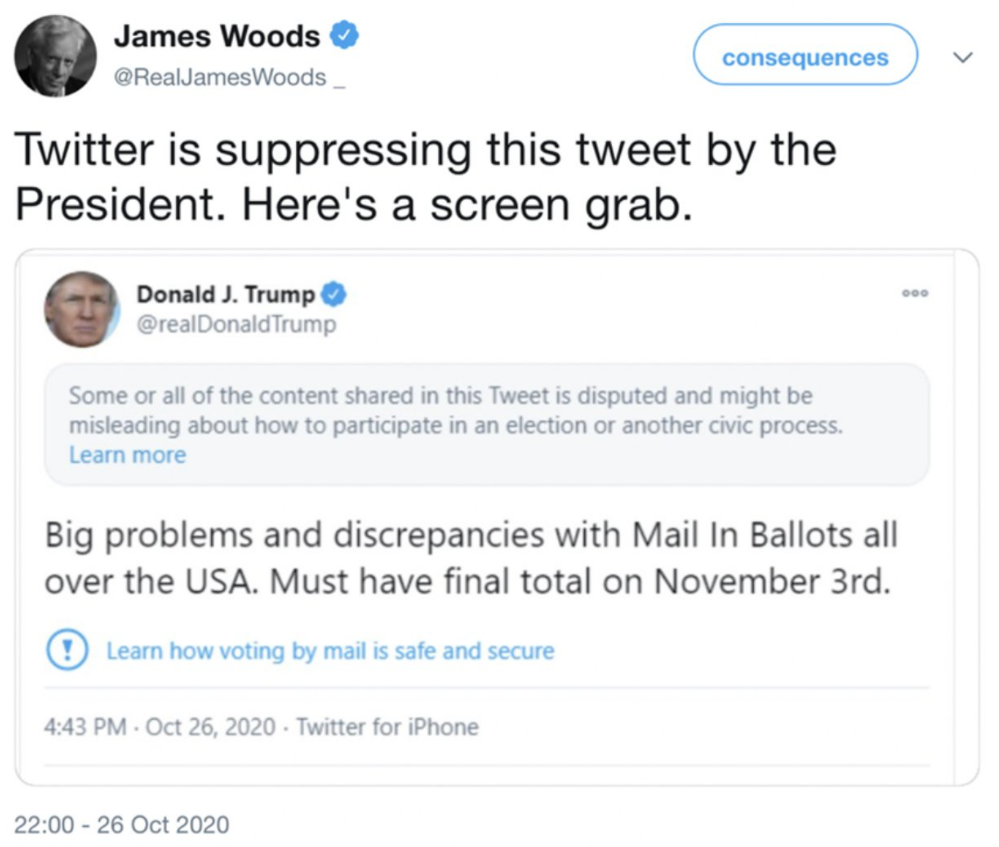

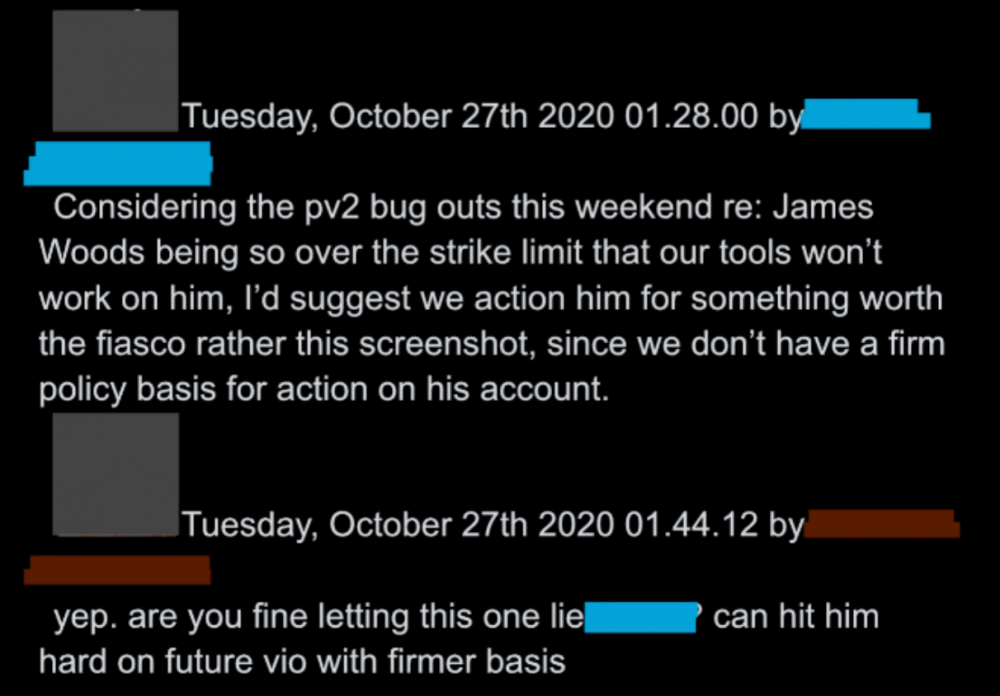

A seemingly innocuous follow-up involved a tweet from actor @realJamesWoods, whose ubiquitous presence in argued-over Twitter data sets is already a #TwitterFiles in-joke.

After Woods angrily quote-tweeted about Trump’s warning label, Twitter staff – in a preview of what ended up happening after J6 – despaired of a reason for action, but resolved to “hit him hard on future vio.”

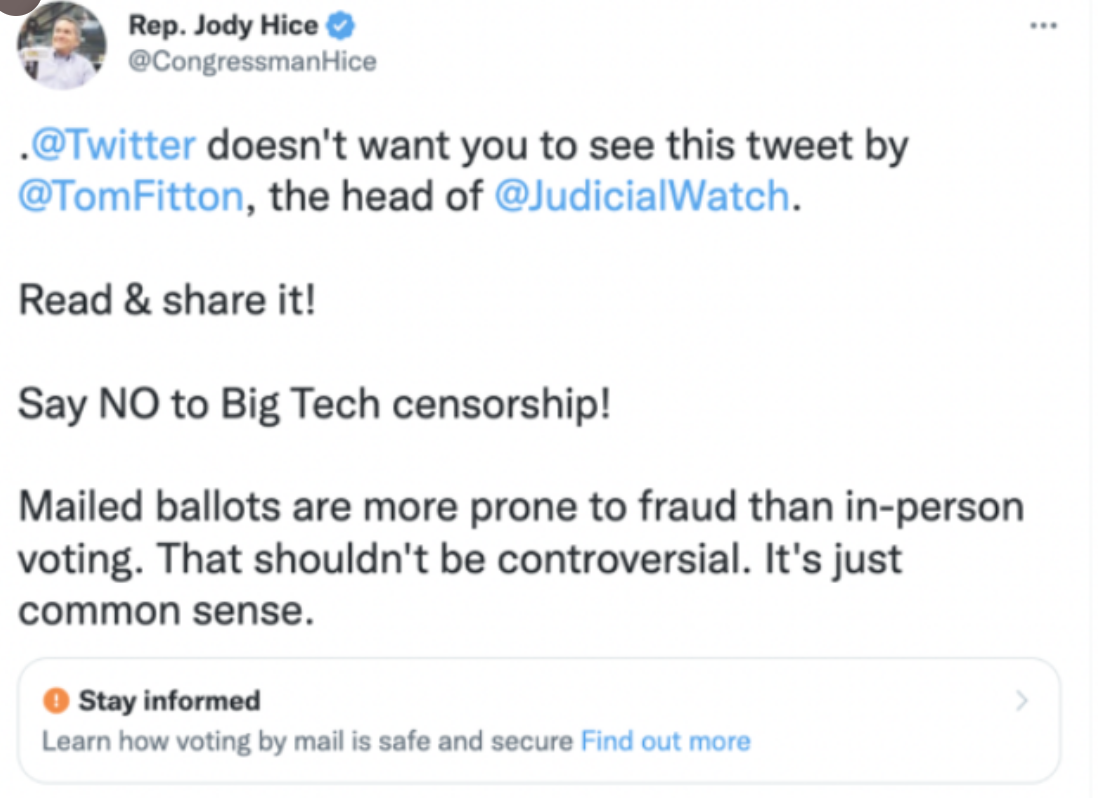

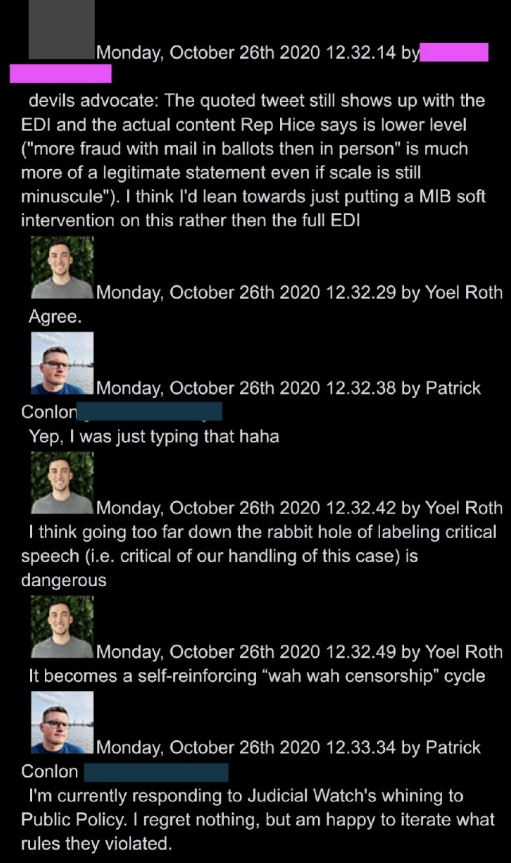

Here a label is applied to Georgia Republican congresswoman Jody Hice for saying, “Say NO to big tech censorship!” and, “Mailed ballots are more prone to fraud than in-person balloting… It’s just common sense.”

Twitter teams went easy on Hice, only applying “soft intervention,” with Roth worrying about a “wah wah censorship” optics backlash:

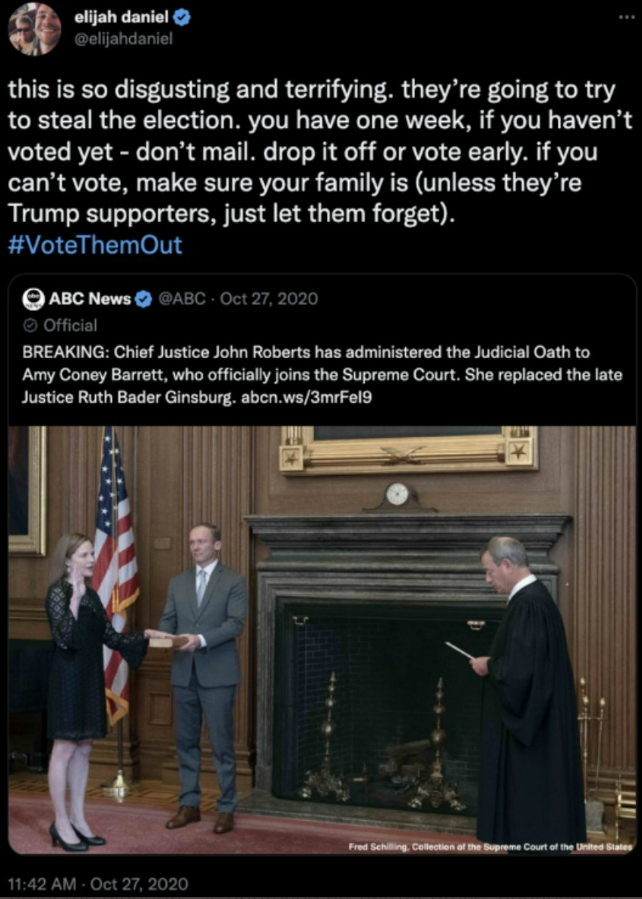

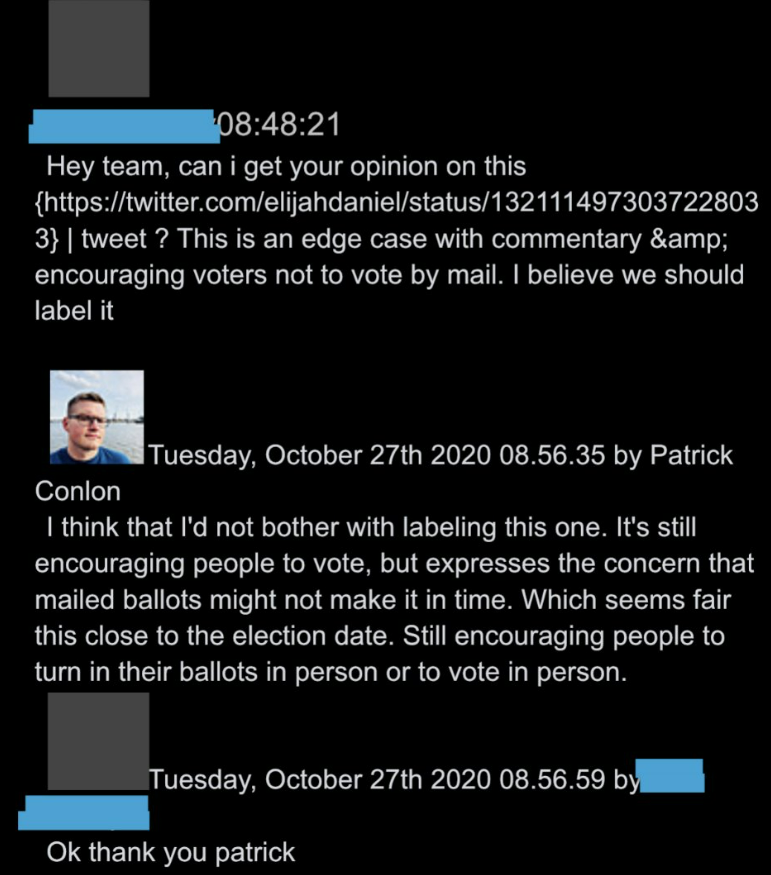

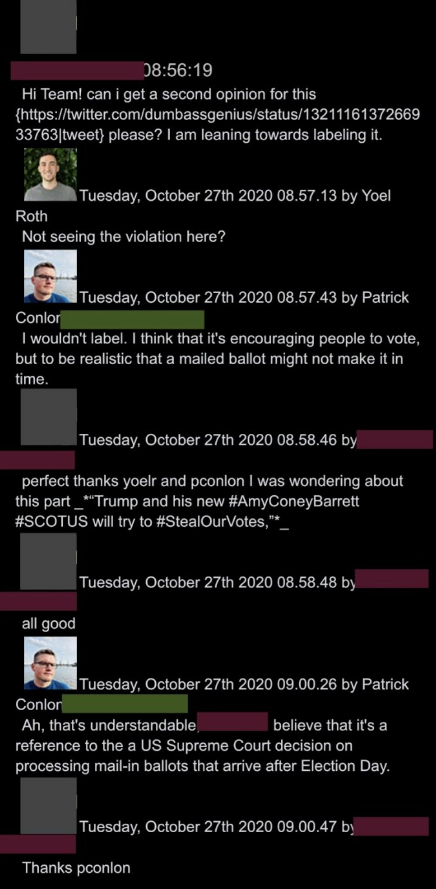

Meanwhile, there are multiple instances of involving pro-Biden tweets warning Trump “may try to steal the election” that got surfaced, only to be approved by senior executives. This one, they decide, just “expresses concern that mailed ballots might not make it on time.”

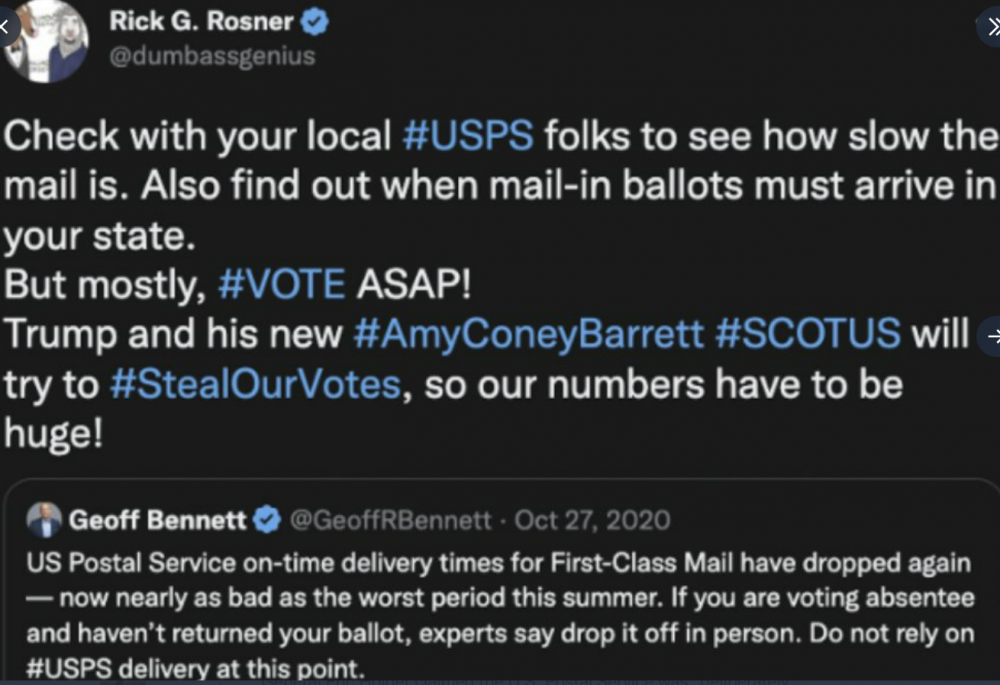

“THAT’S UNDERSTANDABLE”: Even the hashtag #StealOurVotes – referencing a theory that a combo of Amy Coney Barrett and Trump will steal the election – is approved by Twitter brass, because it’s “understandable” and a “reference to… a US Supreme Court decision.”

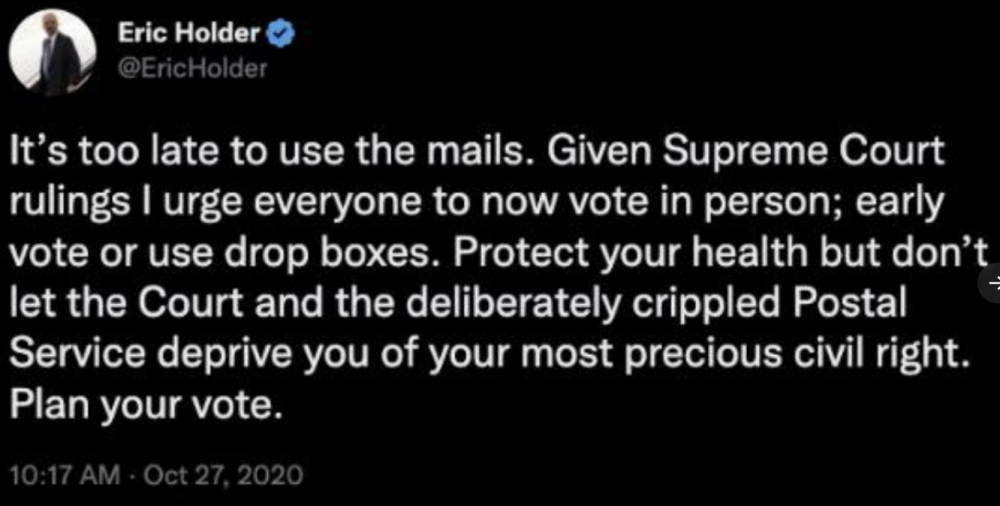

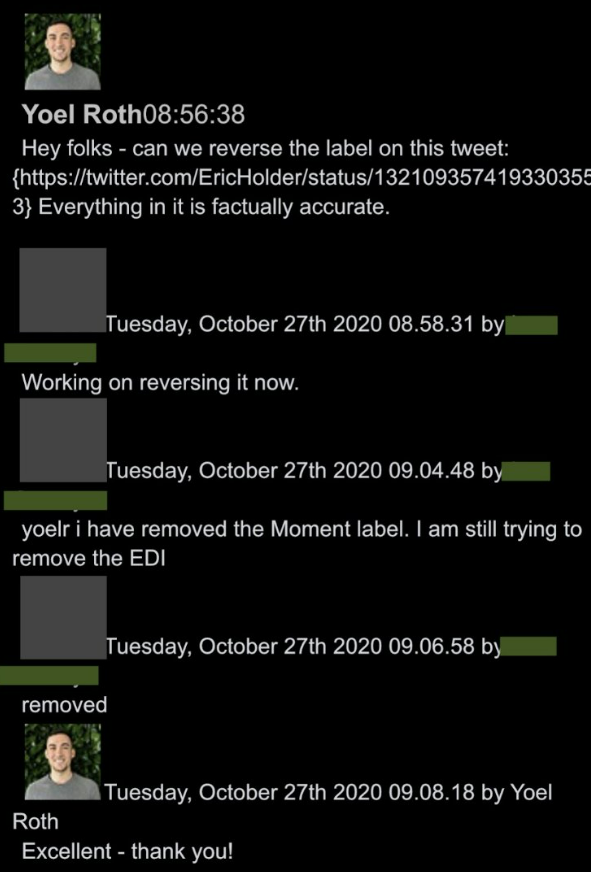

In this exchange, again unintentionally humorous, former Attorney General Eric Holder claimed the U.S. Postal Service was “deliberately crippled,”ostensibly by the Trump administration. He was initially hit with a generic warning label, but it was quickly taken off by Roth.

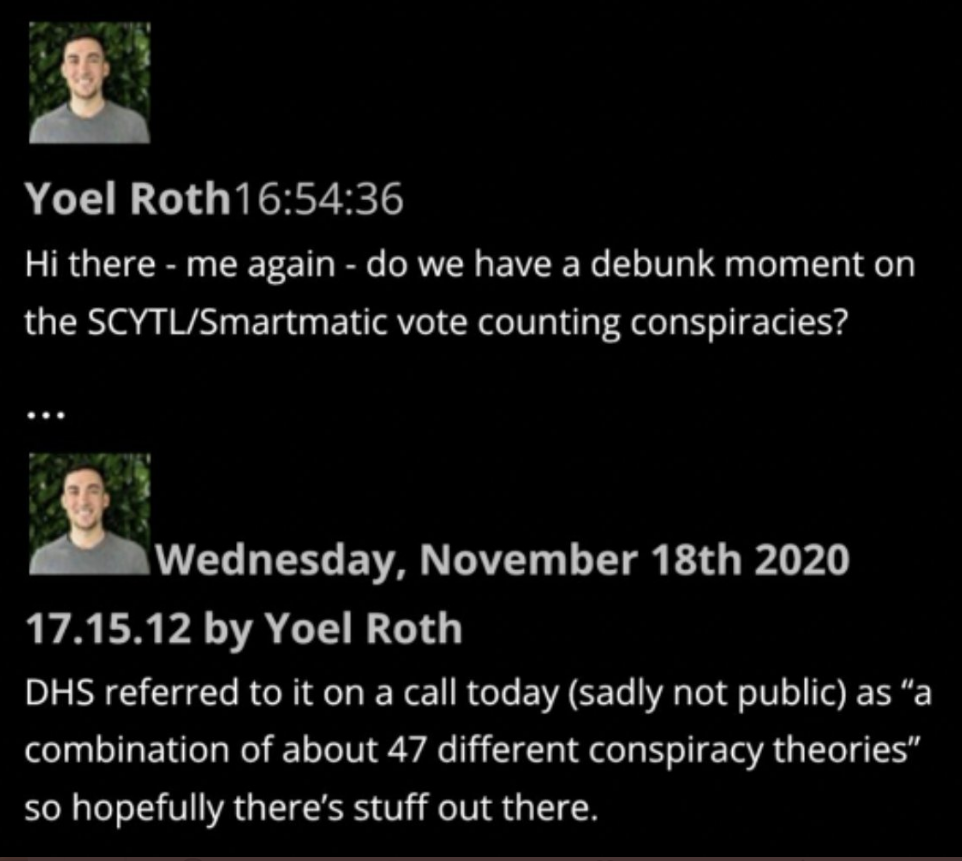

Later in November 2020, Roth asked if staff had a “debunk moment” on the “SCYTL/Smartmantic vote-counting” stories, which his DHS contacts told him were a combination of “about 47” conspiracy theories.

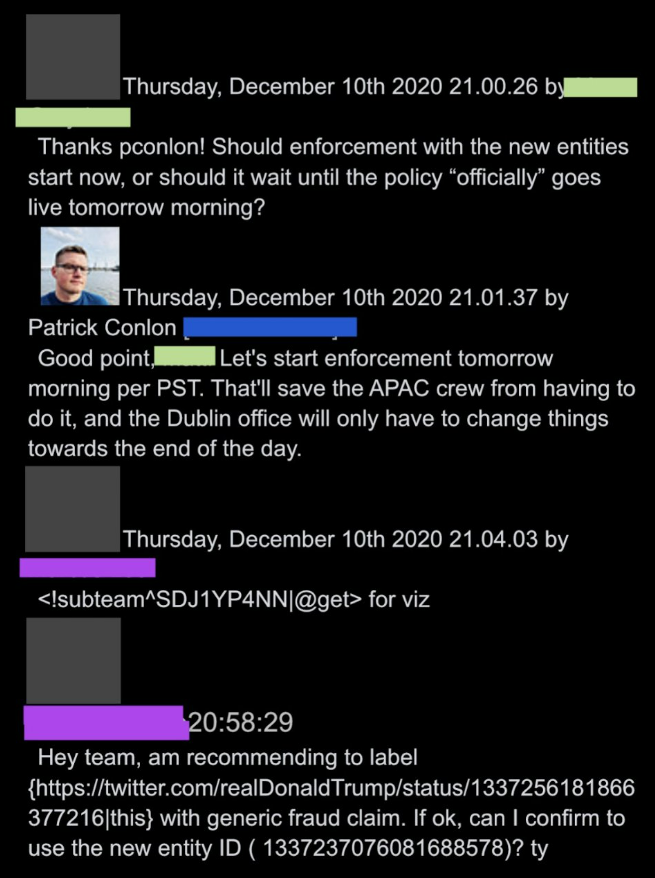

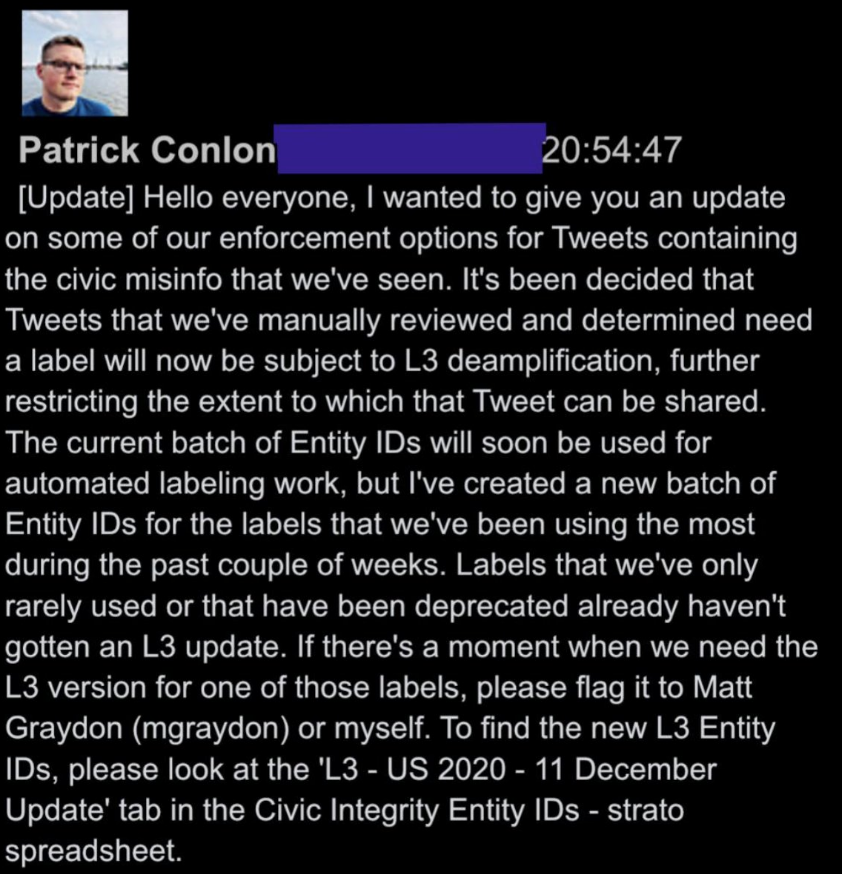

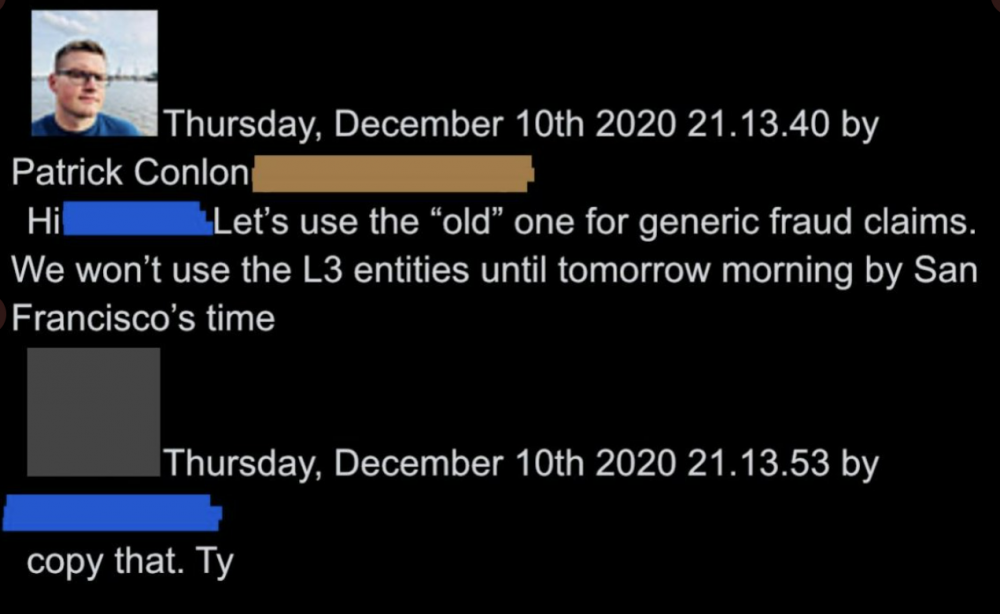

On December 10th, as Trump was in the middle of firing off 25 tweets saying things like, “A coup is taking place in front of our eyes,” Twitter executives announced a new “L3 deamplification” tool. This step meant a warning label now could also come with deamplification:

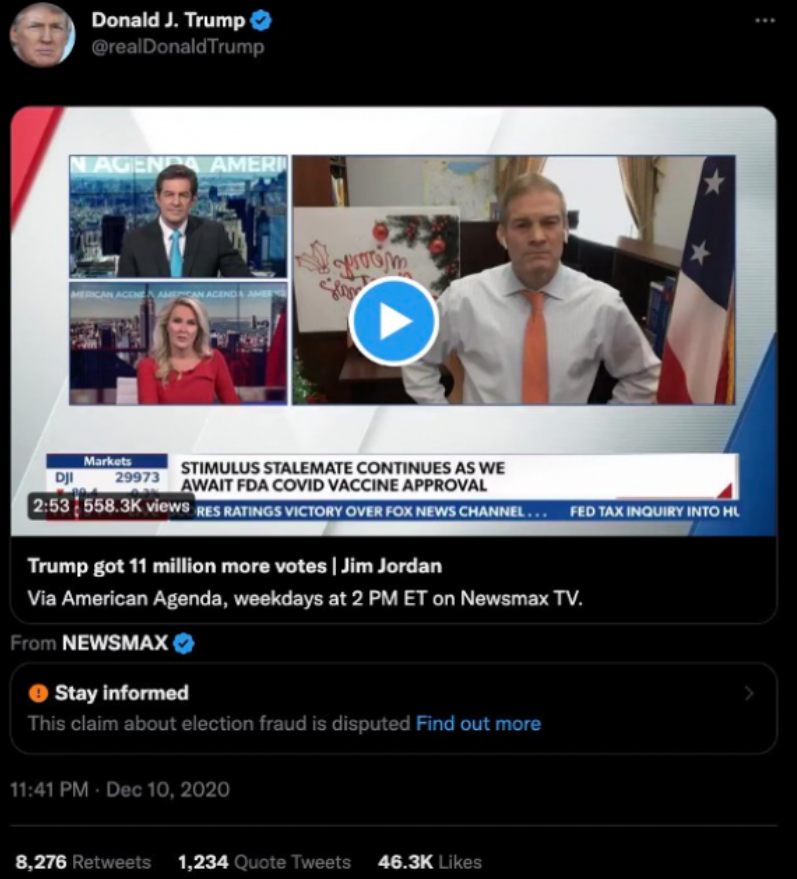

Some executives wanted to use the new deamplification tool to silently limit Trump’s reach more right away, beginning with the following tweet:

However, in the end, the team had to use older, less aggressive labeling tools at least for that day, until the “L3 entities” went live the following morning.

The significance is that it shows that Twitter, in 2020 at least, was deploying a vast range of visible and invisible tools to rein in Trump’s engagement, long before J6. The ban will come after other avenues are exhausted.

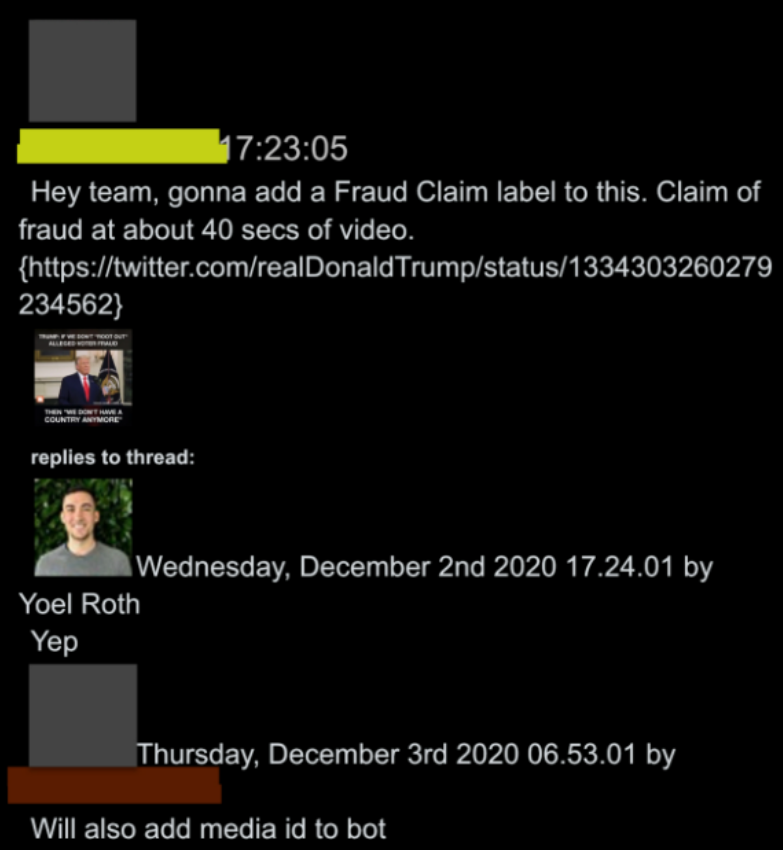

In Twitter docs execs frequently refer to “bots,” e.g. “let’s put a bot on that.” A bot is just any automated heuristic moderation rule. It can be anything: every time a person in Brazil uses “green” and “blob” in the same sentence, action might be taken.

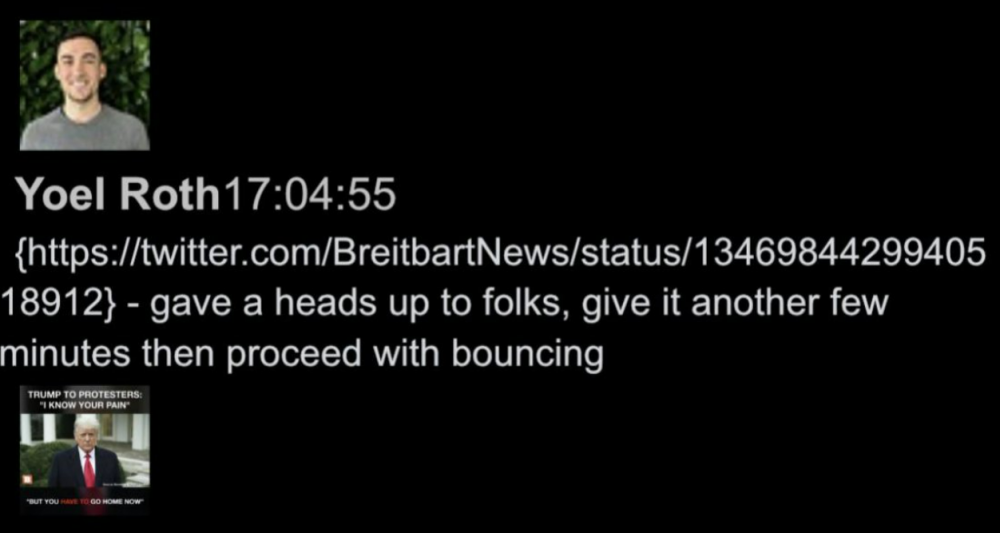

In this instance, it appears moderators added a bot for a Trump claim made on Breitbart. The bot ends up becoming an automated tool invisibly watching both Trump and, apparently, Breitbart (“will add media ID to bot”). Trump by J6 was quickly covered in bots.

There is no way to follow the frenzied exchanges among Twitter personnel from between January 6thand 8th without knowing the basics of the company’s vast lexicon of acronyms and Orwellian unwords.

(To “bounce” an account is to put it in timeout, usually for a 12-hour review/cool-off)

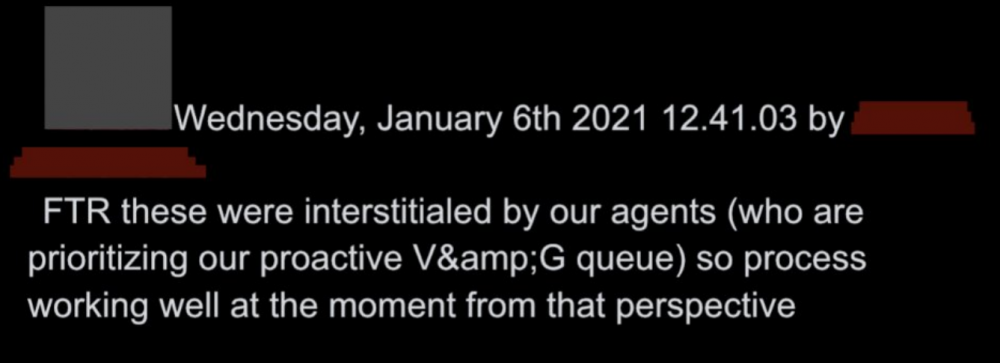

“Interstitial,” one of many nouns used as a verb in Twitterspeak (“denylist” is another), means placing a physical label atop a tweet, so it can’t be seen.

PII has multiple meanings, one being “Public Interest Interstitial,” i.e. a covering label applied for “public interest” reasons. The post below also references “proactive V,” i.e. proactive visibility filtering.

This is all necessary background to J6. Before the riots, the company was engaged in an inherently insane/impossible project, trying to create an ever-expanding, ostensibly rational set of rules to regulate every conceivable speech situation that might arise between humans.

This project was preposterous yet its leaders were unable to see this, having become infected with groupthink, coming to believe – sincerely – that it was Twitter’s responsibility to control, as much as possible, what people could talk about, how often, and with whom.

The firm’s executives on day 1 of the January 6th crisis at least tried to pay lip service to its dizzying array of rules. By day 2, they began wavering. By day 3, a million rules were reduced to one: what we say, goes.

Twitter executives and employees quickly pivoted from “is there a policy violation” to “do we want this information available to the public.” If this isn’t enough of a “smoking gun” for you, just wait. Part 4 is on the way…

Leave a Reply