Why Twitter Surrendered to the Federal Government

In Part 1 of the TwitterFiles, we learned that Twitter was working with politicians, federal agencies, and Biden’s campaign team to censor information on Twitter – specifically as related to Hunter Biden’s laptop and the ensuing New York Post story.

In Part 2, we learned that teams of Twitter employees build blacklists, prevent disfavored tweets from trending, and actively limit the visibility of entire accounts or even trending topics—all in secret, without informing users. In other words, “blacklisting” and “shadowbanning” were real, despite congressional testimony by people like Jack Dorsey claiming otherwise.

In Part 3, we revealed how Twitter employees and directors escalated their censorship campaign in January 2020… and how they effectively threw out the rulebook in favor of their own partisan ideals.

In Part 4, we learned how Twitter executives built the case for a permanent ban – something unprecedented for a world leader up to that point. More importantly, we learned how that “decision” was written in stone before it ever happened.

In Part 5, we uncovered the uncouth truth about what really happened at Twitter when they chose to permanently ban a sitting US president from one of the most-viewed social platforms in the world.

In Part 6, we learned just how closely Twitter worked with government agencies – particularly the FBI – to shut down posts and accounts… all behind closed doors. Twitter’s contact with the FBI was constant and pervasive, as if it were a subsidiary.

In Part 7, we discovered how the FBI & intelligence community discredited factual information about Hunter Biden’s foreign business dealings before the New York Post broke the story about Biden’s laptop… and how the FBI gave Twitter nearly $3.5 million for their cooperation.

In Part 8, we found out how Twitter quietly aided the pentagon’s covert online PsyOp campaign. Despite promises to shut down covert state-run propaganda networks, Twitter docs show that the social media giant directly assisted the U.S. military’s influence operations.

In Part 9, we learned about “Other Government Agencies” (which is the federal codeword for the CIA), and how that agency was intimately involved in the effort to silence dissenting opinions on Twitter and other tech/media platforms.

In Part 10, we began to unwrap the pervasive censorship associated with SARS-CoV-2, including masks, lockdowns, and vaccine safety. Both political parties worked to silence reputable doctors and scientists, which led to injury and death for millions.

In Part 11, we’ll review how and why media – including Twitter – ultimately surrendered to the intelligence community. Moreover, most of this government-mandated censorship was based on rumors and misinformation, with federal agencies unable to support their allegations with hard data.

This story comes from Matt Taibbi. You can read the entire Twitter thread here.

Twitter through the end of August 2017 was on nobody’s radar as a key actor in the Trump-Russia “foreign influence” scandal.

By the second week in October — six weeks later — the company was being raked over the coals in the press as “one of Russia’s most potent weapons in its efforts to promote Donald Trump over Hillary Clinton,” with Clinton herself adding:

“It’s time for Twitter to stop dragging its heels and live up to the fact that its platform is being used as a tool for cyber-warfare.”

What happened in those six weeks? Answering that question is a key to understanding the content moderation phenomenon. In this period, crucial in the company’s history, a pattern was established. Threats from Congress came first, then a rush of bad headlines (inspired by leaks from congressional committees, and finally a series of moderation demands coming from the outside. Once the company acceded, the cycle repeated.

The documents lay out the scheme. You can see how the Russian cyber-threat was essentially conjured into being, with political and media pressure serving as the engine inflating something Twitter believed was negligible and uncoordinated to massive dimensions.

“KEEP PRODUCING MATERIAL”

The timeline started when a fellow tech titan, Facebook, decided in late August 2017 to suspend 300 accounts with “suspected Russian origin.” The move appeared to irritate some Twitter insiders, as Facebook not only shared data with Twitter, but with the Senate Intelligence Committee, where ranking Democrat and Virginia Senator Mark Warner was on an all-out hunt for Russian meddlers.

Twitter’s leaders, anxious to avoid being “dragged into another pitch for an industry wide solution,” as one senior lawyer put it, appeared peeved that Facebook pulled them into the congressional muck. Yet they mistakenly believed the company could still side-step the political/PR minefield, and “keep the focus on FB,” mainly because they were all sure there hadn’t been a big Russia problem on their network:

“No larger patterns.”

“We did not see a big correlation.”

“FB may take action on hundreds of accounts, and we may take action on ~25.”

As the autumn progressed, however, Twitter’s leaders began to realize the Russia thing might hit them no matter what.

An early hint came in a September 8, 2017 piece in the New York Times called “The Fake Americans Russia Created to Influence the Election.”

This was one of many stories that helped the Times win a Pulitzer Prize for exploring “Russian interference in the 2016 presidential election and its connections to the Trump campaign.” Author Scott Shane explained that social media platforms like Facebook and Twitter had been “turned into engines of deception and propaganda.” On Twitter specifically, the Times in conjunction with the cybersecurity group FireEye claimed, “Russian fingerprints are on hundreds or thousands of fake accounts that regularly posted anti-Clinton messages,” adding:

“The fakery may have added only modestly to the din of genuine American voices in the pre-election melee, but it helped fuel a fire of anger and suspicion in a polarized country.”

Twitter employees seemed puzzled by the FireEye piece, but didn’t really worry until the appearance of stories hinting they were being uncooperative with Washington.

“Hi guys,” wrote Public Policy VP Colin Crowell on September 23, 2017. “Just passing along for awareness the writeup here from the WashPost today on potential legislation (or new FEC regulations) that may affect our political advertising.”

The article, “Facebook’s openness on Russia questioned by congressional investigators,” mostly focused on Facebook, but like the Times piece included a few shots across Twitter’s bow. It noted congressional “investigators also are pushing for fuller answers from Google and Twitter, both of which may have been targets of Russian propaganda efforts.”

Later that month, Twitter staff, led by Crowell, met with Warner and his staff, shared what the company believed to be true, that they had no coordinated Russian interference issue on their platform.

Not only did Warner not like this answer; he gave Twitter a fierce media paper-training, holding an instant press conference to voice his displeasure.

“Their response was, frankly, inadequate on almost every level,” Warner told reporters. Reuters added that Warner said the Twitter briefing was “mostly derivative of a presentation earlier this month given by Facebook,” and “lacked thoroughness.”

The Warner presser hit Twitter like a bomb. Gallows humor filled inboxes.

“Well these are good headlines…” joked a communications officer, passing along an email with the subject line, INADEQUATE ON EVERY LEVEL.

“#Irony,” mused Crowell, upon receipt (the day after the presser) of an e-circular from Warner’s re-election campaign, asking for “$5 or whatever you can spare,” to “help Mark hit his quarterly fundraising goal.”

In a circular to other senior executives about his meeting with Warner, Crowell explained that Warner “has political incentive to keep this issue at top of the news, maintain pressure on us and rest of industry to keep producing material for them.” He added that although Warner’s public posture was contentious, the private atmosphere was more of a “collaborative spirit.”

He also said congressional Democrats were “taking cues from Hillary Clinton,” who that same week told a Stanford audience she was the victim of a “virtual Watergate.”

Crowell explained further that the company was being “hurt” by outside academics and researchers, who “tap our API to pull together flawed reports painting the bot/Russian troll problem as a significant presence on Twitter.” He added:

“It was evident in the room with staff investigators that these researchers had already briefed the committees and asserted Twitter is a major problem. These studies are also cited in recent media stories.”

There are mentions throughout Twitter’s email record that fall of studies by a range of researchers “tapping” the data Twitter and Facebook shared with Congress. The company took special note of former FBI Counterintelligence agent Clint Watts, whose work on the Foreign Policy Research Institute’s “Hamilton 68” project gave reporters a public “dashboard” for tracking “Russian Disinformation on Twitter.” Its web page featured a crude illustration of Vladimir Putin tossing bunches of red Twitter symbols into the ether:

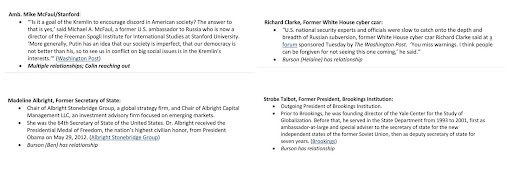

Part of the reason Twitter hired Burson-Marsteller was because the company boasted a stable of former government officials — including many from the Obama and Clinton administrations — who had relationships with the Democratic Party’s loudest Russia hawks. Burson even sent over a “third parties” outreach document, detailing which members of their team had contacts with Strobe Talbott, Madeleine Albright, Richard Clarke, and former ambassador to Russia Michael McFaul, among others.

Those documents aren’t scandalous, but they’re valuable in a “how the world works” sense. Hit with a firestorm of negative press, coming mainly from Democratic Party partisans (along with a few Republicans), Twitter was able to turn down the heat a tiny bit by spending $50,000 a month on a contract with consultants and lobbyists close to their accusers.

A tiny bit wouldn’t be enough, however.

“NO EVIDENCE OF A COORDINATED APPROACH”

In a growing panic over its PR problems, Twitter formed a “Russia Task Force” to investigate itself. Despite the pressure to produce “material,” reports coming in from the Task Force in the coming weeks kept coming back snake eyes:

October 13: “We have found suspicious accounts which demonstrate our investigation strategy is working, however we see no evidence of a coordinated approach, all of the accounts found seem to be lone-wolf type activity (different timing, spend, targeting, <$10k in ad spend).”

October 16: “First phase of analysis finished over weekend via manual review of ~700 accounts. Found ~15 suspicious accounts (i.e. state targeting, pro trump), but no relationship to each other, mostly SMB, and low total spend (<$10k).”

October 18: “First round of RU investigation shared with legal/comms/PP yesterday. The results suggest 15 high risk accounts, 3 of which have connections with Russia, although 2 are RT.”

October 23: “Finished with investigation… Completed 2500 full manual account reviews, we think this is exhaustive analysis… We’ve identified 32 suspicious accounts and only 17 of those are connected with Russia, only 2 of those have significant spend, one of which is Russia Today, and the remaining are <$10k in spend…”

Analysts at Twitter were coming to the conclusion that outsiders were using a kind of academic magic trick to conjure the Russian threat. Researchers took low-engagement, “spammy” accounts with vague indicia pointing to Russia (for instance, retweet activity), and identified them as not only Russian, but specifically as creations of the media’s favorite villain, the Internet Research Agency of “Putin’s chef,” Yevgeny Prigozhin.

Twitter went along, in many cases to make a temporary press problem go away. In the case of the Buzzfeed story, for instance, Trust and Safety chief Yoel Roth explained:

“I’d prefer to keep our relationship with Buzzfeed generic and positive, i.e. “thanks for the tip, we took action on it even if it doesn’t mean exactly what you think” rather than quibbling about their methods and conclusions.”

Twitter ultimately suspended a few dozen more accounts identified by Buzzfeed as Russia-linked. Right away, executives wondered if this was the right move, correctly guessing that giving in once would open the floodgates for similar requests.

“If Buzzfeed and a small UK University have managed to successfully turn up a list of accounts in TOS violation that resemble accounts identified as IRA ones,” wrote one communications staffer, “we can expect that several other third parties are running the same exercise and we’ll see this sort of incoming repeating itself over the coming months.”

“Given we’ve now suspended all accounts,” wrote another, “we will take a hit in the press that moves from BuzzFeed to more establishment publications. We’ll work to contain it.”

They couldn’t contain it. When Twitter didn’t “produce” fast enough, Congress cranked up the pressure, leaking to multiple news outlets the larger original data sets that Facebook and Twitter turned over.

“The committees appear to have leaked the account names,” wrote Monje on November 22.

Now, instead of 22 accounts, reporters at papers like the Wall Street Journal and New York Times were asking about thousands. This was exactly what was predicted internally after the Buzzfeed episode about a spread to “more establishment publications.”

“INTERNAL GUIDELINES”

Before they knew it, Twitter personnel were fending off headlines like the New York Times piece, “Russian Influence Reached 126 Million Through Facebook Alone.” The Times was now not only trumpeting the data as exposing the “breadth” of the Kremlin efforts to divide America, but perhaps a road that might lead back to the Trump campaign:

“The new information goes far beyond what the companies have revealed in the past and underline the breadth of the Kremlin’s efforts to lever open divisions in the United States using American technology platforms, especially Facebook. Multiple investigations of Russian meddling have loomed over the first 10 months of the Trump presidency, with one leading to the indictments of Paul Manafort, the former Trump campaign chief, and others on Monday.”

This is the same data in which Twitter’s “Russia Task Force” found “only 2” significant accounts, “one of which” was RT. It didn’t matter. Once Congress put out a bigger number of “shadowy” accounts, news outlets were able to write any story they wanted. Journalists moreover learned they could produce easy headlines by taking lists of names given to them by congressional staffers, or “identified” as suspicious by researchers like Hamilton 68 or FireEye, rerouting them back to Facebook or Twitter, asking for comment.

“Reporters now know this is a model that works,” is how one Twitter communications officer put it.

Twitter General Counsel Sean Edgett testified along with counterparts at Facebook and Google before the Senate on November 1, beginning a long series of sojourns by tech executives to the Hill, where both Democratic and Republican legislators would grill them about their plans for preventing the “sowing of discord.” There, he announced Twitter had “launched a retrospective review to find Russian efforts to influence the 2016 election through automation, coordinated activity, and advertising.”

At the same time, Twitter leaders in private were settling on the posture the company would adopt more formally going forward. In public, they would maintain independence, and only remove content “at our sole discretion.” Privately, the company would “off-board” anything “identified by the U.S. intelligence community as a state-sponsored entity conducting cyber-operations.”

Publicly, we remove you at our discretion. Privately, theirs. This “internal guidance” note is a key moment in the email record, marking Twitter’s formal internal decision to allow the intelligence community to guide the moderation process. The arrangement would evolve into a formal partnership in the coming years.

“DUTY TO MONITOR”

This sequence of the #TwitterFiles shows how Twitter quickly adjusted its public evaluation of the foreign interference scandal to fit political demands, then just as quickly gave in to demands to let media outlets, NGOs, and ultimately, government agencies dictate its content moderation procedures.

In doing so, Twitter allowed the U.S. government to use the same playbook European Union officials used years before to bring tech companies under heel: first threaten firms with new legislation and increased regulation, then allow the firms to escape financial penalty by ceding control over content.

Twitter knew this pattern from experience, and via researchers who sometimes advised its board. In August 2017, executives circulated a Notre Dame Law Review article by law professor Danielle Citron called Extremist Speech, Compelled Conformity, and Censorship Creep, which talked about the very recent experience of Facebook, Microsoft, Google, and Twitter in Europe. After Islamic terrorist bombings in Paris and Brussels in 2015 and 2016, the companies were told by EU officials they needed to clamp down, or else. Citron wrote:

“The message from EU regulators was clear. If companies failed to remove extremist or terrorist content, they would face new legal obligations, including a duty to monitor content, civil penalties, and criminal liability.”

Just over a year earlier in Europe, in May of 2016, the companies in conjunction with the EU signed a “Code of Conduct on Countering Illegal Hate Speech Online,” formalizing the idea of a “duty to monitor content.”

Roughly the same thing took place in the U.S. in the fall of 2017, but the process was informal and mostly secret. Instead of ISIS bombings and Brexit, the predicate for action was the election of Donald Trump and theories of Russian meddling. No company was exempt, as Twitter found out that fall, and went on to understand more keenly afterward.

Leave a Reply